East Gallery:

The show will consist of real-scale objects cast incontent-related materials.

Jana Sterbak

Mercer Union

Toronto

by Jeanne RandolphVanguard, December 1982

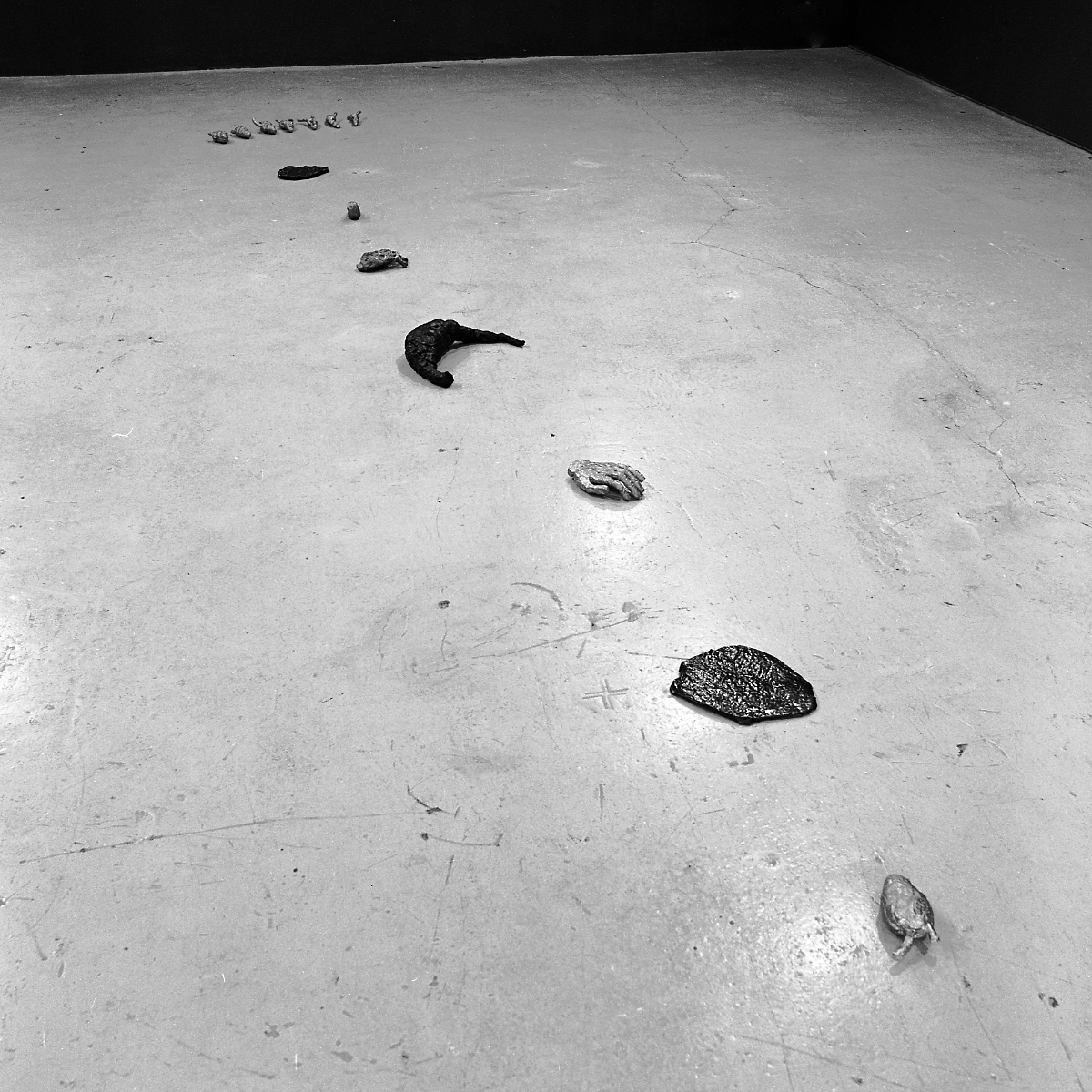

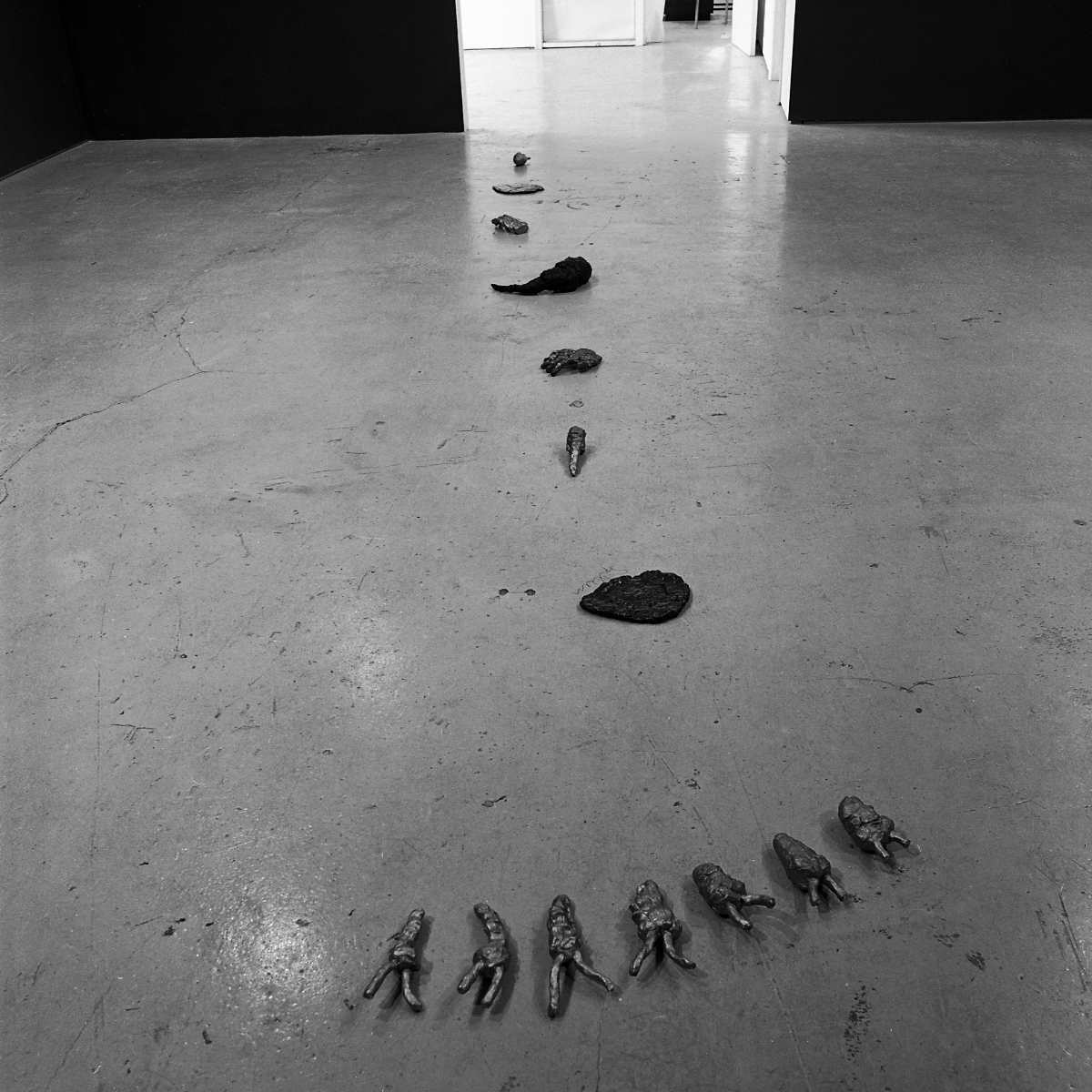

Even considering that art galleries are seldom frequented by lummoxes, most of the sculptures in this exhibition are so petite and vulnerable someone might inadvertently stomp on them, meek and squiggly upon the floor. At the entranceway are three little lumpy lead feet. Elsewhere, a trail of thirteen anatomical simulacra struggles toward a doorway: seven hardened hearts, a squarish slice of red metal spleen, a silvery bone-like thing, two small stiffened hands, a puny black rubber stomach and a flabby slice of rubber liver. On one of the walls the bronze sculptures sit side by side, semblances of human ears, except that instead of ear canals they have gnarled, spindly protuberances. The exhibition includes in addition two photographic works and the fact that the interior walls of the main, specially-built display area are a very serious, mineral blue. The construction of this area did not appear to imply that architectural elements were contributing anything to the interpretation of these sculptures; rather, the redesign of the gallery space seemed simply to allow a direct attention to the autonomous, tangible integrity of the separate sculptural projects. The evolution of the meaning of these works, it seems, begins in their tangible qualities; the paradox of central value to these sculptures is that an intimation of something immaterial could be accessible to the sense of touch. It is as if the ephemeral could be felt with a finger if only tactile sensitivity were intensified to an extreme, or that metaphysical can be palpated unseen in the physical, the inert quickened through contact with the hand. The cool gummy surface of the liver object, when it is prodded or picked up, for example, shudders in one's grasp, though not with slimey hysterics. What has happened is that in poking at such a pulpous object, one's own subjective shiver ends up becoming an objective feature of the things being handled. What has been aroused by the tactile presence of these bodiless organs is uncertainty as to where subjective experience leaves off and perceptible substance begins. These sculptures fully embody the promise given in the exhibition's title - Objects as Sensation.

Malleable materials, bronze, lead, rubber, have been distorted into homely ersatz body bits for a fluently expressive, indeed canny, articulate purpose, however: this exhibition has another dimension, the other half of its title, the metaphor: Golem. The mystery that is fundamental to sculpture that inanimate material can be enlivened, has in this instance been equated with a supernatural event, the artificial human being, the golem, upon whom life is bestowed by a force outside the laws of nature. The metaphor of the golem, transfixing the imagery and the experience of the work, is quite touching. Interpretations about the nature of sculpture, of language, even of the Self, enchant the imagination.

The latter possibility is nevertheless the most sensitive. The wry, unassembled body parts inevitably invite the implication of the artist's experience of herself or of her creative production into the golem metaphor. Standing over what is shy yet nevertheless adroit evidence that the artist had "spilled her guts,'' the symbolic anatomy seems to have the potential to signal a tragedy of intimate proportion for either golem or artist. An assertion from one of the Kleinian psychoanalysts comes close to articulating the kind of spiritual jeopardy that may be inherent in this kind of imagery - ''All creation is really a re-creation of a once loved and ruined object, a ruined internal world and self." The Kleinians ruminated upon the possibility that ''the ruined self" is in a lifelong struggle to be wholly good; a universal psychological realily that the best art must inevitably embody, they said.

Maybe Golem: Objects as Sensation does waken an anxiety about the ruined self's fate; the artist's expression of extreme vulnerability, by choosing the symbolic objects she did, and by choosing the metaphor of the golem with its unresolved relationship to the natural world, could have been grisly. Perhaps some viewers shunned the contact they would have had to make with such content. But the scale of the work has a perverse daintiness that divens the viewer from real depression or disgust. Whether the golem is about to coalesce and receive his life's breath, or whether the golem and all he stands for may just have fallen quite apart, these sculptures are remarkably amenable to the viewer's imaginings.